By Torild Skard

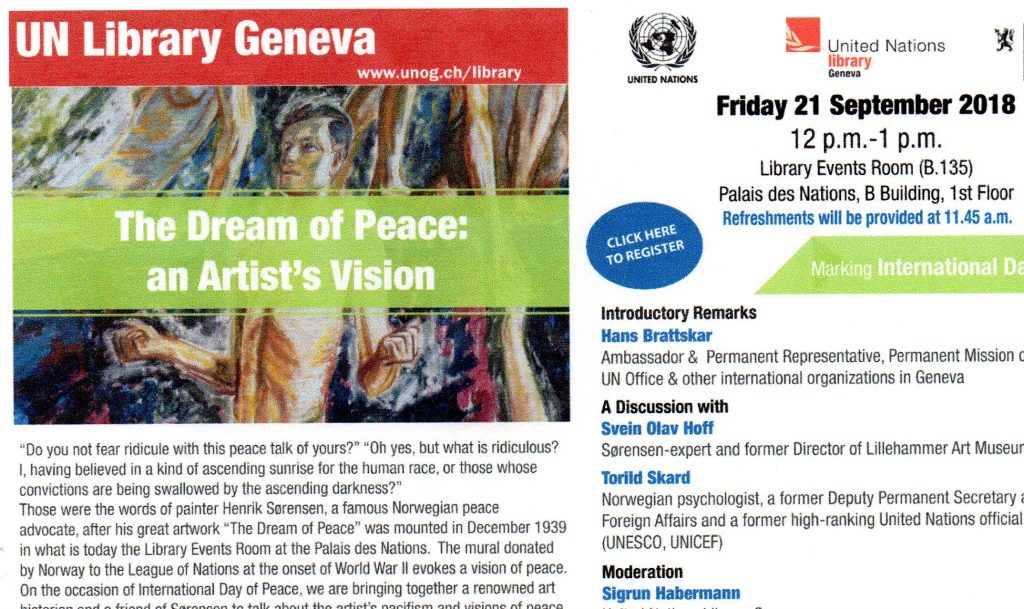

UN Library 21 Sept 2018

The Norwegian Minister of Foreign Affairs who gave this large mural to the League of Nations, was my grandfather, Halvdan Koht. He was my mother’s father, and I grew up with him. After the Second World War we lived with my grandmother, my parents, brothers and sisters in a bungalow near Oslo. Here, in the living room, there was a large painting hanging on the wall with the inscription “For The Dream of Peace”. I was fascinated by it. In brown and rust red colours it depicted a naked man climbing up a steep hill – and he was, oh, so tired, but he kept on climbing, nevertheless. How far it was to reach his goal, I had no idea. But I was sure he would not give up. And there were some light green spots at the top of the picture.

I was not preoccupied with the large mural in Geneva, though my grandfather told me about it. For me the painting at home was so complete, that I could not perceive it only as a detail of a much larger work of art.

The painting at home gave me courage and strength. When I was mobbed at school, and when I met resistance or obstacles in things I wanted to do, then I would go home and find comfort looking at Henrik Sørensen’s painting. The man had a dream – of peace – and he did not give up.

Henrik Sørensen gave the painting to my grandfather “with thanks” because of the role my grandfather played in assigning him the task of making the mural. Sørensen had contacts in wide circles across the political spectrum and knew both the conservative C.J.Hambro and my socialist grandfather well. During my childhood Sørensen often came home to us to see my grandfather. Then the whole family had dinner together. Sørensen – or Søren as we called him – enjoyed being with children, and we looked forward to his visits. He was often dressed informally with his hair a bit in disarray and came smiling, stretching his arms towards us. We joked and called him “the gentle troll”. He often played with us, friendly and warm-hearted, making sure we did not quarrel or fight.

I remember especially once when I was 12 or 13 years old and was helping prepare the dinner. I was going to serve beer I had brewed myself, but my brothers and sisters teased me, saying that the beer was no good. When Henrik Sørensen heard this, he at once wanted a glass of the beer. My brothers and sisters protested, but Søren insisted. And he got a glass. He took it and drank, slowly, tasting the beer carefully. He sucked his lips and then said seriously: “I think it is the best beer I have ever tasted!” I will never forget it.

Sørensen was also an absorbing artist – with such a varied collection of works, from portraits and landscapes, to religious and political subjects. Our family often went to admire his pictures, in and around Oslo, and I never got tired of looking at his paintings.

And to me the decision of the Norwegian state to give the League of Nations a large mural made by Henrik Sørensen was a good example of fruitful collaboration despite political differences. When the League was created after World War I, it was no simple matter for Norway. In fact, we joined the organization with 100 votes for and 20 against in Parliament. The Labor Party was against, because the League was not based on disarmament. Four MPs to the right also voted against, because the organization was part of the Treaty of Versailles, which they thought was an immoral peace alliance. The opposition to the right was headed by C. J. Hambro.

Hambro was one of the most important politicians in Norway at the time and became leader of the Foreign Policy Committee in Parliament. During several international negotiations he collaborated closely with my grandfather, although he was member of the Labor Party. My grandfather was professor of History at the University, did extensive research nationally and internationally and spoke many languages.

Hambro was one of the most important politicians in Norway at the time and became leader of the Foreign Policy Committee in Parliament. During several international negotiations he collaborated closely with my grandfather, although he was member of the Labor Party. My grandfather was professor of History at the University, did extensive research nationally and internationally and spoke many languages.

Once Norwegian membership in the League of Nations was a reality, Hambro used all his energy to make the work of the League as effective as possible. And my grandfather had the same approach when he became Minister of Foreign Affairs. So they continued to collaborate across party lines.

As I grew up, I also became involved in international cooperation and often visited UN offices, among others in Geneva. But I was always busy with different matters and did not think of the Sørensen mural before suddenly one day in 2014 I heard a lecture by a Norwegian art historian in Oslo about “The Dream of Peace”. And to my surprise she ended her lecture by stating that photos of the painting unfortunately only existed in black and white and, in fact, she did not know if the mural still existed or not.

I lost my breath. It was not possible that art experts in Norway did not know what had happened to one of Henrik Sørensen’s masterpieces! Next time I went to Geneva, I was determined to find out. The tourist guides in the Palais des Nations shook their heads. They had never heard of “The Dream of Peace”. When I insisted, they agreed to check and found out that the painting actually could be seen in the library, not far from the tourist reception in the large building. But it was excluded from ordinary sightseeing, because the visitors would disturb the studies.

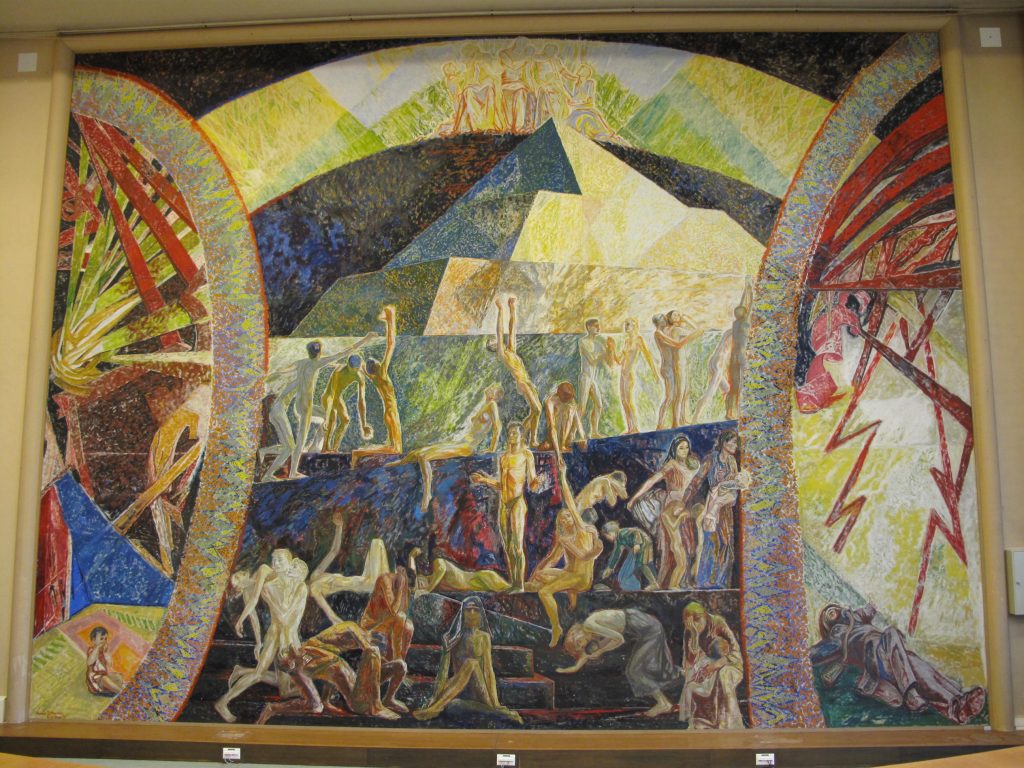

When I went to the library and asked to see «The Dream of Peace”, there was no problem. I was immediately taken to the next room. There was the mural. Completely intact and much larger than I expected. So many human beings striving and struggling – oppressed men and unhappy women. The man on my painting at home nearly disappeared in the mass of people. He was toiling at the bottom of the huge work of art. At the top, above the pyramid, there was light and peace with mothers and children from various continents. The despair and the hope – it was so overwhelming and touching that tears came to my eyes.

My guide was a friendly and sympathetic man, and I told him about Søren and the painting I had at home. He listened attentively, and then he burst out: «You have known Henrik Sørensen! How wonderful! His painting gives us the vision for our efforts here at the UN, but information about the work has been lost. We are not even sure if the painting is completed or not.”

The lack of knowledge both in Oslo and Geneva about such a wonderful and important work of art shocked me. So I started searching, acquiring and spreading information in collaboration with Henrik Sørensen’s only son, Sven Oluf Sørensen, who still lived at the time. Unfortunately, he died recently at an advanced age. Sven Oluf was a very respected professor of physics and made great efforts to promote his father’s art. He among others established two Henrik Sørensen museums and wrote a biography of his father.

Sven Oluf was assisted by a number of friends, among which some are here today, and I have worked with them, with the Norwegian mission in Geneva and with the staff at the UN library. I have found and read the biographies of Henrik Sørensen written by our speaker here today Svein Olav Hoff in addition to Sven Oluf Sørensen and translated the relevant texts about “The Dream of Peace” from Norwegian to English. Then I translated into Norwegian from the two thick books that I received from the UN library about the art in the Palais des Nations. I am very happy about the international cooperation we have had. Partners both in Oslo and Geneva have actively followed up. A photo of “The Dream of Peace” is now exhibited in the Peace Research Institute PRIO in Oslo and we are here in the Palais des Nations on the International Day of Peace to appreciate the contribution of Henrik Sørensen to the efforts for peace. Thank you, thank you! And I hope many people will be inspired by the painting to fight for peace.

Mer informasjon:

– Dream of Peace UNOG folder-1

– Honouring the Norwegian Painter and Pacifist on the International Day of Peace 2018